Entertaining a natural fascination with the warfare and weapons of Ancient Greece, we will linger a little while longer on this exciting topic and enjoy a wonderful lineup of interesting guest posts in the next few weeks.

Embedded like a hidden gem in last week’s guest post by Richard Vallance Janke, A Mycenaean Chariot in the Knossos Armory, a mention of his colleague Rita Roberts enticed me to pay a visit to her website. What a treat!

A retired archaeologist living in Crete, Rita Roberts has my deepest respect and admiration for her wonderful accomplishments in translating ancient Mycenaean Linear B script. Under Richard’s excellent mentorship, Rita completed a diploma in Linear B studies and she is now pursuing an undergraduate degree.

Lately working with Linear B tablets from Knossos regarding Mycenaean military affairs, Rita is well on her way to becoming an expert on the subject. The following guest post is her essay comprehensively outlining current knowledge on the topic of Mycenaean chariot construction.

Offering a rich complement in the search for everything related to Achilles and his divine shield, I am very sure we will see more archaeological coverage from Rita here on TheShieldofAchilles.net.

The Construction of the Mycenaean Chariot, by Rita Roberts

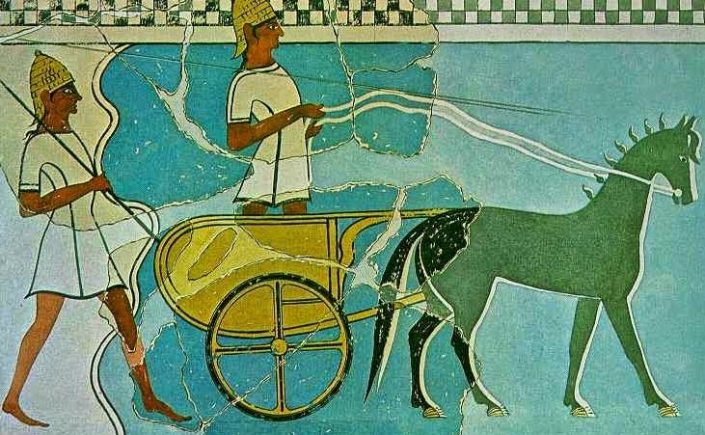

Even though we have examples shown on frescoes and pottery vessels depicting chariots, it is difficult to say for sure how a Mycenaean chariot was constructed. These examples however, only give us mostly a side view, which presents a problem. What we really need to find, is an example which shows all angles, for us to get a better understanding of the Mycenaean chariot's construction. It is hard to visualize these chariots as they actually appeared in Mycenaean times, 1400-1200 BC. But they were certainly built for battle worthiness when needed.

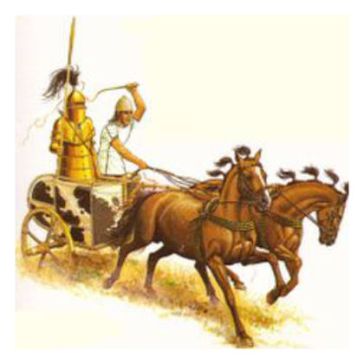

Bronze Age war chariot

It is to be noted that the Mycenaean military, as that of other ancient civilizations, such as those of Egypt in the Bronze Age, the Hittite Empire, the Iron Age of Athens and Sparta, and later still, of the Roman Empire, most certainly would have gone to great lengths in manufacturing all parts of the chariots to be battle worthy, strong and resistant to wear, and of the highest standards within the limits of technology available to them in Mycenaean times. The chariot, most likely invented in the Near East, became one of the most innovative items of weaponry in Bronze Age warfare. It seems that the Achaeans adopted the chariot for use in warfare in the late 16th century BC, as attested to on some gravestones as well as seals and rings.

Gold signet ring from shaft grave IV in Mycenae dated LH II (about 1500 BC). Source: Salimbeti’s The Greek Age of Bronze Chariots

It is thought that the chariot did not come to the mainland via Crete, but the other way around, and it was not until the mid 15th century BC that the chariot appears on the island of Crete, as attested to by seal engravings and the Linear B Tablets. The Achaean chariots can be divided into five main designs which can be identified as, “box chariot”, “quadrant chariot”, “rail chariot” and “four wheeled chariot.” None completely survived, but some metallic parts and horse bits have been found in some graves and settlements, also chariot bodies, wheels and horses are inventoried in several Linear B tablets.

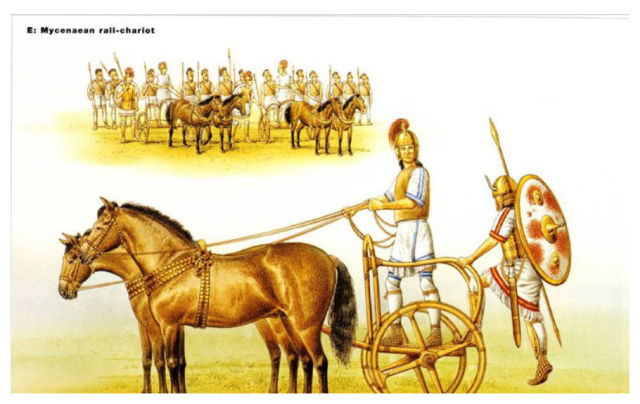

Mycenaean rail chariot

The “rail chariot” was a light vehicle which featured an open cab and was more likely used as a means of transport than as a mobile fighting vehicle. The “four wheeled chariot,” used since the 16th century BC, was utilized throughout the late Helladic time. Both the “rail chariot” and the “four-wheeled chariot” continued to be used after the end of the Bronze Age.

Attic Black-Figure Amphora depicting Bronze Age chariot

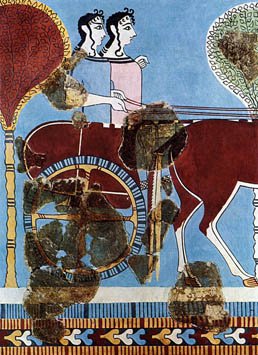

Based on some hunting scenes and armed charioteer representations on pottery vessels and Linear B tablets, there is no question that the chariots were used in warfare as a platform for throwing javelins (or thrusting long spears), as a means of conveyance to and from battle and, on fewer occasions, as a platform for a bow-armed warrior. These warriors could have fought as cavalry or a force of mounted infantry, particularly suited to responding to the kind of raids that seem to have been occurring in the later period. Some thoughts on the construction of the Mycenaean chariot: As we cannot be absolutely sure how the Mycenaean chariot was constructed, we have to use pictorial examples, leaving us little choice, other than that of resorting to a close examination of the pottery vessels and frescoes depicting them, and whatever other sources are available. So I have chosen the beautiful “Tiryns Fresco” 1200 BC as an example of the construction and design of the Mycenaean chariot, although some points differ in other depictions on various other frescoes.

Lovely Tiryns Chariot Fresco. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Mycenaean chariots were made to be drawn by two horses attached to a central pole. If two additional horses were added, they were attached on either side of the main team by a single bar fastened to the front of the chariot. The chariot itself consisted of a basket with a rail each side and a "foot board" for the driver to stand on. The body of the chariot rested directly on the axle connecting the two wheels. The harness of each horse consisted of a bridle and reins, usually made of leather, and ornamented with studs of ivory or horn. The reins were passed through collar bands or yoke, and were long enough to be tied around the waist of the charioteer, allowing him to defend himself when necessary. The wheels and basket of the chariot were usually of wood, strengthened in places with bronze, the basket sometimes covered with wicker wood. The wheels had four to eight spokes. Most other nations of this time, the “Bronze Age,” had chariots of similar design to the Greeks, the chief differences being the mountings.

Mycenaean Chariot from Pylos Fresco. Source: ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Α΄ ΓΥΜΝΑΣΙΟΥ

The components needed to build a chariot: (w/Linear B translations in bold) • Chariot = iqiya • Axle = akosone • Wheels = amota • Rims of Wheels = temidweta • Willow wood = erika • Elm wood = pterewa • Bronze = kako • Spokes • Leather = wirino • Reins = aniya • Pole • Rivets • Studs • Spokes • Ivory = erepato • Horn = kera • Foot board = peqato • Gold = kuruso • Silver= akuro

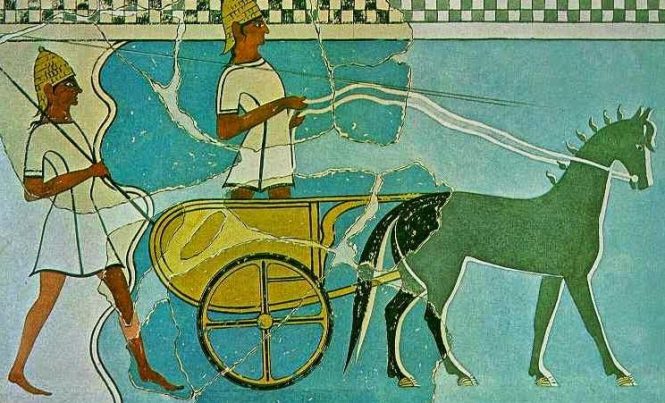

Achaean Small Box Chariots with an example of the horse harness

The cabs of these chariots were framed in steam bent wood and probably covered with ox-hide or wicker work, the floor consisting more likely of interwoven raw-hide thongs. The early small box-chariots were crewed either by one single man or two men, a charioteer and a warrior. The small box-chariot differ in terms of design from the Near Eastern type. The four spoke wheels seem to be standard throughout this period. Rita Roberts, Haghia Triada, Crete

–For additional info on the chariots of Ancient Greece, visit Salimbeti’s excellent page, The Greek Age of Bronze Chariots (many of the images used in this post were found there)

–Also see M. Lahanas’ HellenicaWorld.com for another excellent page about Ancient Greek chariots.

–Top Image Title and Credit:

Mycenaean Chariot from Pylos Fresco. Source: ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Α΄ ΓΥΜΝΑΣΙΟΥ

Thank you so much for this post Kathleen. I am pleased you are so interested and following my progress with the Linear B scripts. Thanks to my teacher Richard Vallance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure Rita! I really admire your efforts and accomplishments – so interesting and so challenging!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fasinating post Kathleen & Rita…. So interesting to read about the mycenaean chariots … I was particularly thrilled to learn about the five designs they can be divided into, as I´d have thought we were referring to just one type, otherwise. I wouldn´t have thought that bronze was used to for certain parts (“The wheels and basket of the chariot were usually of wood, strengthened in places with bronze”)

The fact that Linear B tablets allowed us to figure out details proves how important and useful those initial ways of writing were, indeed.

A fascinating reading!!!!… Thanks so much for sharing… sending love & best wishes 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Aquileana, I agree, even though the Linear languages aren’t very exciting – not really literature, but more administrative – like any ancient writing they are fascinating for the glimpses they provide into that long ago world and it’s interesting to learn what was important enough to keep records of (at least for us History fans!). Love and best wishes backatcha! ;^)

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] er elsta listræna afrekið, eru skreytt með Hómerískri táknmynd sem sýnir atriði úr lífi Akkillesar, grísku hetju Trójustríðsins. Myndlist móður Achillesar Thetis, kynnir sonur hennar með […]

LikeLike

[…] identifies four main types of chariot used by the Mycenaeans: the “box chariot”, the “quadrant […]

LikeLiked by 1 person