Following our in-depth looks at chariots in Ancient Greece and the historical records of the Mycenaean Palace Armory of Knossos, now we’ll continue on to Homer’s Iliad and take a closer look at the famous warrior heroes of the Trojan War.

The following is a guest post by Barry C. Jacobsen, a former US Army Special Forces operator (“Green Beret”) who has worked on television and film projects as a historical adviser, stunt choreographer, actor, and historical commentator and adviser.

Helping hold down the fort on the television show, The Deadliest Warrior, Jacobsen served as both Historical Advisor and Associate Producer.

“My passion,” states Jacobsen, “is warriors, weapons, and all aspects of military history.”

This is surely the understatement of the year, as I’m sure you’ll agree when you check out the exceptional way Jacobsen covers the Trojan War in this magnificently illustrated post:

ART OF WAR: HEROES OF TROY AND MYCENAE

Originally published on The Deadliest Blogger: Military History Page

By Barry C. Jacobsen

Much of our perception of history is influenced by the artists who have drawn and painted scenes from out of the past. This is the second in a series in which Deadliest Blogger looks at historical armies and warriors through the images artists have given us.

The Trojan War was a seminal event in both Greek and Roman history and legend; and few episodes in Classical mythology have attracted more attention from artists, writers, or filmmakers than this famous war.

In their immortal tales the epic poets Homer and Virgil describe the ten-year war between the Greeks and the Trojans; and the wanderings of the Trojan hero Aeneas and the refugees from Troy to Italy. While these tales were accepted as history by both the Greeks and the Romans; post-renaissance scholars largely dismissed them as myth. It was not till the work of archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, who did the initial excavations at both Hisarlik in Turkey (site of ancient Troy) and at Mycenae that the underlying truth behind the legends began to emerge. Since Schliemann, continuing archaeology has confirmed and expanded our knowledge of events first described by Homer. We now know that the site of Troy was continuously occupied over many centuries, and archaeologists have uncovered not one city, but many; each built on the ruins of the previous.

Most scholars and archaeologists agree that Troy VII was the Troy of Homer.

Most scholars and archaeologists agree that Troy VII was the Troy of Homer.

The world of Homer’s heroes (as well as the other heroes of Greek “mythology”) was that of the late Bronze Age. Most scholars now place the Trojan War somewhere between 1260 BC and 1120 BC. This was a world in which petty-kings ruled small fiefdoms from the lofty heights of hilltop fortresses. These “palaces” were much akin to later Medieval castles of Europe: miniature towns crowded within and around mighty “Cyclopean” walls.

Ruins of Mycenae, fortress-palace of the House of Atreus; perched on a rocky spur.

Ruins of Mycenae, fortress-palace of the House of Atreus; perched on a rocky spur. Artist reconstruction of the citadel of Mycenae in the time of Atreus and Agamemnon.

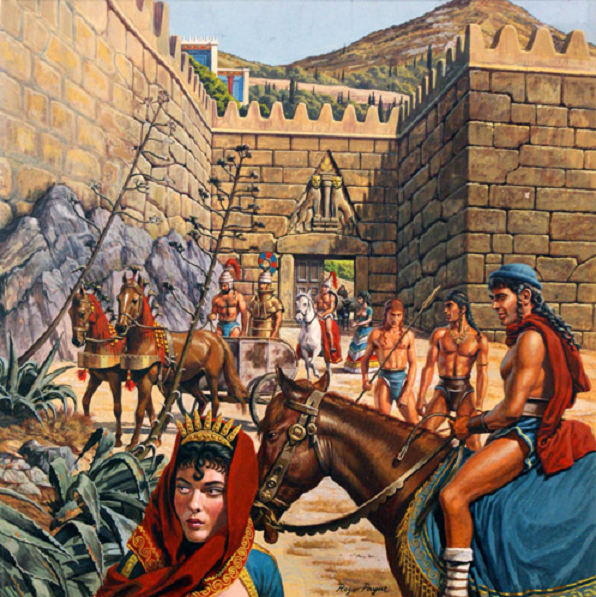

Artist reconstruction of the citadel of Mycenae in the time of Atreus and Agamemnon. Lion Gate at Mycenae.

Lion Gate at Mycenae. Detail from artist and historian Peter Connolly’s illustration of the Lion Gate and protecting bastion.

Detail from artist and historian Peter Connolly’s illustration of the Lion Gate and protecting bastion. The Mycenaean Age citadels were the center of political life in the Bronze Age Aegean. This lively image brings to life the Lion Gate at Mycenae; main entrance into the fortified palace-complex of the Atreidae kings.

The Mycenaean Age citadels were the center of political life in the Bronze Age Aegean. This lively image brings to life the Lion Gate at Mycenae; main entrance into the fortified palace-complex of the Atreidae kings. Though girded with grim stone walls, the palaces within the citadels were spacious centers of everyday life for the ruling class.

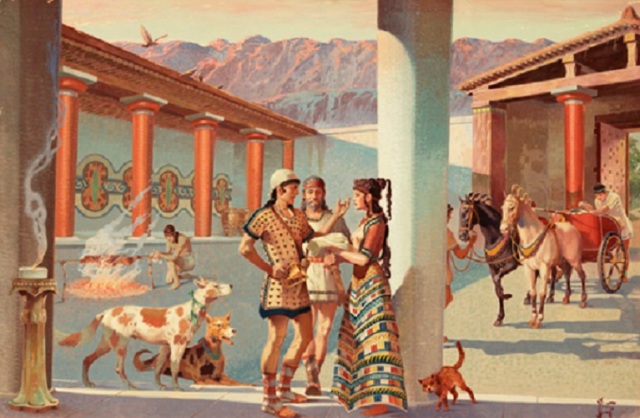

Though girded with grim stone walls, the palaces within the citadels were spacious centers of everyday life for the ruling class.

The megaron (great hall) of a Mycenaean palace.

The megaron (great hall) of a Mycenaean palace.

The Greeks of the Bronze Age are called “Achaioi” (Achaeans) in the Illiad, and Ahhiyawa in Hittite sources. In the ancient eastern Mediterranean world the High King of Mycenae was one of the four principal political leaders of the day; alongside the Hittite King, the Assyrian (or Babylonian) King, and the Pharaoh of Egypt. The kings of Mycenae (according to Homer of the House of Atreus, the Atreidae) were “first-among-equals”, the paramount kings of the Achaean warlords.

Greece in the Bronze Age was dotted with hilltop citadels, home to the “King” and his armed followers, his bureaucrats and courtiers, and their numerous families.

Greece in the Bronze Age was dotted with hilltop citadels, home to the “King” and his armed followers, his bureaucrats and courtiers, and their numerous families.

At Troy, it was Agamemnon son of Atreus who led the Achaeans to victory. Together with his father, Atreus, he had established the dominance of Mycenae over the other Achaean strongholds. Perhaps as part of this process, either Atreus or Agamemnon arranged a marriage alliance with the powerful king of Sparta, Tyndareus; in which Agamemnon married the king’s eldest daughter Clytemnestra, and his brother, Menelaus, married the younger one, Helen. When Tyndareus died without living male heirs, Menelaus ascended to the throne of Sparta at Helen’s side. However, her abduction/elopement with the Trojan prince, Paris placed his rule there (and Mycenean dominance) at risk. This was the legendary trigger for the Trojan War. However, it is quite likely that hostilities had been going on between Troy and Mycenae for some time; and this was merely the final straw that launched the two powers into all-out war.

Discovered by Schliemann in Tomb V of the Acropolis of Mycenae, the gold so-called “Mask of Agamemnon dates to an earlier king of Mycenae, from the 15th century BC.

Discovered by Schliemann in Tomb V of the Acropolis of Mycenae, the gold so-called “Mask of Agamemnon dates to an earlier king of Mycenae, from the 15th century BC.

Agamemnon as portrayed by actor Brian Cox, in Troy (2004).

Agamemnon as portrayed by actor Brian Cox, in Troy (2004).

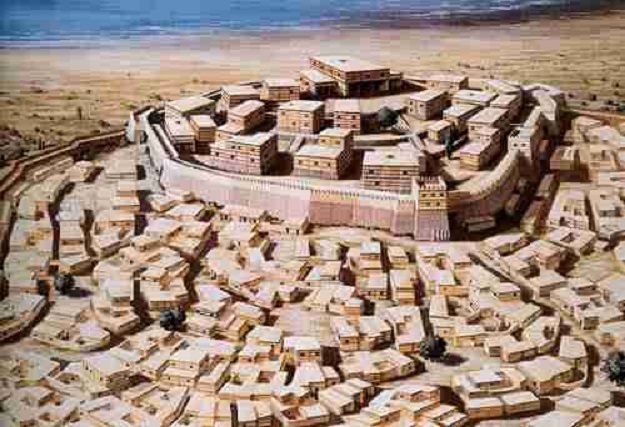

Troy (or Ilios) was a powerful city-state; and some-time vassal of the Hittite Empire (known in their records as Wilusa). Troy was not unlike Mycenae: a town surrounding a hilltop palace and temple complex, strongly walled and defended. Located on the southwest shore of the Hellespont (the modern Dardanelles), it was perfectly situated to dominate this narrow choke-point; entrance-and-exit to the Black Sea. The Achaean states of Greece traded in the Black Sea region for grain and gold; and paid the kings of Troy a toll for passage through.

Troy was perfectly placed to take advantage of Black Sea Trade. While today the old harbor has been silted up by the outflow of the Scamander River (modern Karamenderes), in the Bronze Age the citadel of Troy overlooked a harbor. No doubt Trojan picket ships, beached below the walls, rowed out to interdict ships passing by, exacting tolls and tariffs. Control of this trade route was a contributing factor to the Trojan War.

Troy was perfectly placed to take advantage of Black Sea Trade. While today the old harbor has been silted up by the outflow of the Scamander River (modern Karamenderes), in the Bronze Age the citadel of Troy overlooked a harbor. No doubt Trojan picket ships, beached below the walls, rowed out to interdict ships passing by, exacting tolls and tariffs. Control of this trade route was a contributing factor to the Trojan War.

Ships such as this carried both warriors and trade throughout the Aegean World. When not otherwise engaged at home, Mycenaean warlords took to the sea to raid and trade as opportunity arose.

Ships such as this carried both warriors and trade throughout the Aegean World. When not otherwise engaged at home, Mycenaean warlords took to the sea to raid and trade as opportunity arose.

When a Trojan princess was abducted by the petty-king of Salamis, Telamon (father of the hero Ajax) relations deteriorated between Troy and the Achaeans. Perhaps this led to the Trojans placing higher tolls on Greek ship passing through to the Black Sea, or blocking access to such trade completely; setting the stage for war. Certainly the practice of women-stealing went both ways and was wide-spread throughout the Mycenaean world.

Artist’s rendering of what Troy may have looked like. (Below) Troy in film: from 1956’s, “Helen of Troy”; and (bottom) from “Troy” (2004)

Artist’s rendering of what Troy may have looked like. (Below) Troy in film: from 1956’s, “Helen of Troy”; and (bottom) from “Troy” (2004)

The warriors who followed the great lords of the citadels were semi-professional feudal warriors; owing loyalty and service (likely in return for sustenance or land of their own) to the “kings” (who was sometimes called the wánax) of the citadels. These armored warriors rode chariots into battle, and were known by the Greek term heroes; literally meaning “protector” or “defender”; the source of our own word “hero”. These well-armed and armored “heroes” guarded the citadels and the land from raiders; and ventured forth on raids and expeditions of their own, gaining “word fame” as their exploits were recorded by court bards. Meanwhile, the average person worked the land as a serf or peasant; and followed the “Heroes” to war as ill-trained “spearmen” .

In the 15th century, Mycenean Greek chariot heroes wore ponderous panoplies of banded bronze, extending to their knees. This is an example from Dendra in the Argolid; made of bronze sheets shaped into large plates and bands. It reflects a warrior who was more apt to stay mounted in his chariot, rather than fight on foot.

The helmet mounted on the Dendra Panoply is made of boar’s tusks, sewed onto a cap of leather.

Duel between heroes, 14th century.

Panoply and equipment of 15th/14th century “Heros”

Troubles between Troy and the Achaean states of Greece went back a full generation before the famous Trojan War of the Iliad. According to legend, the hero Heracles sacked Troy in retaliation for the city’s king, Laomedon, refusing to pay him for a service previously rendered (killing a monster, according to the legend). Heracles killed the king and put the baby, Priam, on the throne. Interestingly, Troy VI, shows signs of destruction by earthquake. The legend has Heracles breaking down its gate with his mighty club. Could legend and fact here meet? Perhaps the historic archetype for the legendary hero took advantage of an earthquake collapsing or weakening one or more of the gates of Troy; and, arriving by sea with a band of raiders, broke into and seized the citadel?

Killing the king, Heracles then exacted a tribute from the city in return for leaving. His friend and companion, Telamon of Salamis, took for his prize Hesione, daughter of Laomedon and sister of Priam.

Heracles, clad in the skin of the Nemean Lion, extorts the prostrate Trojans for tribute. Note that under the lion skin he wears a panoply similar to the Dendra suit. (Artist: Giuseppe Rava)

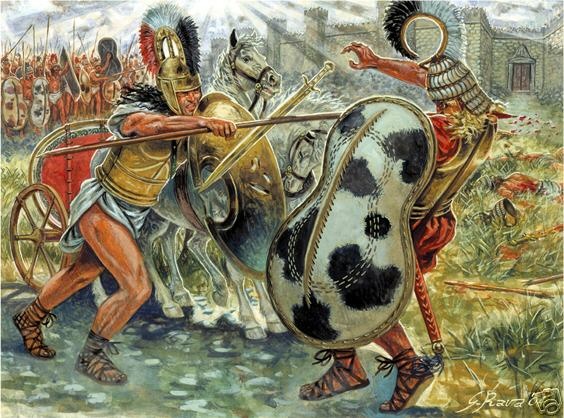

By the 13th century, the armor had evolved. Gone were the clumsy skirts of bronze; leaving only cuirass protecting the warrior’s torso. This allowed for much greater freedom of movement; particularly if the heroes had to fight on foot. If descriptions in the Iliad can be taken as representative of Mycenaean Age combat, heroes of the 13th/12th century rode their chariots into combat (driven by a driver/squire). They exchanged javelin fire with other heroes similarly mounted; or speared footmen as they passed them. At some point, they dismounted to fight duels on foot; again, usually against other, opposing “heroes”.

13th century BC vase from Mycenae. This contemporary representation of Mycenaean warriors of the Trojan War era is among the best depictions of how the “heroes” may have looked.

Legend has it that the Trojan War was started by the abduction (or elopement) of Helen, queen of Sparta, by the Trojan prince, Paris.

In Homer’s Iliad, the war between the Greeks (Achaeans) and the Trojans lasted 10 years. In truth, it would have been a tremendous logistical feat to maintain a besieging army on the sandy plains of Troy for that long. Nor would the warrior-elite dare leave their citadels, wealth, fields and families undefended for so long. A more likely scenario is that Trojan interference with the Black Sea trade led to a 10 year war; in which the Achaeans made regular or periodic raids on the Troad and against Trojan allies. The Iliad focuses on the last, tenth year. It is probable that Agamemnon’s host landed in force only then; and beleaguered Troy in that year.

The Greeks landing was not unopposed; but the Trojans were driven from the beach. Though scholars debate where the Greeks landed, the most likely place was at Besika Bay; on the west coast of the Troad opposite the island of Tenedos. This sandy stretch was sheltered by the Sigean Ridge; and would have allowed easy access to the sea and communications back home. The alternate site, on the north shore, would have placed the Greek camp in the marshy delta of the Scamander River; and too close beneath the walls of Troy for security.

Once the Greek camp was established, the fighting shifted to the Scamander plain. There, regular skirmishes occurred between Trojan and Achaean forces. The bulk of the peasant/townsmen spearmen, who had little training and no armor, took little part accept as victims. The fighting was mostly between the armored “heroes”; fighting on foot or from their chariots. When the hapless spearmen got in the way “of their betters”, they were cut down like sheep.

Once the Greek camp was established, the fighting shifted to the Scamander plain. There, regular skirmishes occurred between Trojan and Achaean forces. The bulk of the peasant/townsmen spearmen, who had little training and no armor, took little part accept as victims. The fighting was mostly between the armored “heroes”; fighting on foot or from their chariots. When the hapless spearmen got in the way “of their betters”, they were cut down like sheep.

One such duel was between Paris and Helen’s husband, Menelaus. After throwing spears at each other, the two warriors closed with swords. Menelaus’ sword broke over Paris’ helmet, stunning the Trojan prince. In fury, the Spartan king grabbed Paris by the horsehair crest of his helmet and dragged him toward the Greek lines; in the process strangling him with his own chin-strap. Fortunately for Paris, the strap broke and he was able to scramble away to safety. (Illustration by Peter Connolly)

One such duel was between Paris and Helen’s husband, Menelaus. After throwing spears at each other, the two warriors closed with swords. Menelaus’ sword broke over Paris’ helmet, stunning the Trojan prince. In fury, the Spartan king grabbed Paris by the horsehair crest of his helmet and dragged him toward the Greek lines; in the process strangling him with his own chin-strap. Fortunately for Paris, the strap broke and he was able to scramble away to safety. (Illustration by Peter Connolly)

In another such duel, the greatest warrior among the Trojan heroes, prince Hector son of Priam faced Ajax son of Telamon. The heroes began by hurling spears at each other, in which exchange Hector was wounded. Ajax next picked up and hurled a large rock at his opponent, which stove-in Hector’s bull’s hide shield. Despite this, Hector fought on and the fight ended in a draw. Both fighters exchanged gifts, and parted with admiration of each other.

In another such duel, the greatest warrior among the Trojan heroes, prince Hector son of Priam faced Ajax son of Telamon. The heroes began by hurling spears at each other, in which exchange Hector was wounded. Ajax next picked up and hurled a large rock at his opponent, which stove-in Hector’s bull’s hide shield. Despite this, Hector fought on and the fight ended in a draw. Both fighters exchanged gifts, and parted with admiration of each other.

Greatest of all the heroes at Troy was Achilles, son of Peleus. “Sacker of Cities”, he led many successful raids on Trojan allied cities during the ten year war. His greatest duel was against Hector. Though a noble and gallant warrior, Hector proved no match for Achilles. Enraged at Hector’s recent killing of his friend, Patrocles, Achilles desecrates the Trojan’s body by dragging it behind his chariot. He later relents and returns the corpse to Hector’s father, Priam, for proper burial. Homer’s Iliad ends with Hector’s funeral.

Patrocles borrowed Achilles armor and, disguised as the great hero, led a Greek attack on the Trojans. Killed by Hector, his body was then stripped and Achilles armor taken as trophy. In one version (captured here by Peter Connolly) Patrocles drives the Trojans back within their walls, and is killed attempting to storm the battlements.

Hector stripped Achilles’ armor from the corpse of Patrocles. Son of a goddess, Achilles’ armor is replaced by the Gods themselves with a magnificent panoply.

Achilles slays Hector. (Illustration by Giuseppe Rava)

Achilles drags Hector’s body. (Illustration by Peter Connolly)

Achilles drags Hector’s body. (Illustration by Peter Connolly)

The duel between Achilles and Hector, from “Troy” (2004)

The war continues, and after slaying other notable Trojan heroes Achilles is himself killed with a poisoned arrow; shot by Paris. The arrow strikes Achilles in the heal; the poison leading to his death.

After the death of Achilles, the Achaean hero Odysseus came up with a plan to infiltrate a small group of heroes into the walls of Troy; from where they could clandestinely infiltrate the city and open the gates to the Greek army. This device took the form of a hollow wooden horse; into which a dozen heroes climbed.

After the death of Achilles, the Achaean hero Odysseus came up with a plan to infiltrate a small group of heroes into the walls of Troy; from where they could clandestinely infiltrate the city and open the gates to the Greek army. This device took the form of a hollow wooden horse; into which a dozen heroes climbed.

To “sell the ruse”, the Achaean host burned their camp and departed by sea. A slave was left, to tell the Trojans that a pestilence had broken out in the Greek camp; and both sick and war-weary, they had given up the fight. However, Agamemnon’s fleet had merely sailed out of sight; sheltering behind the nearby island of Tenedos. The Trojans found the wooden horse in their deserted camp. Told that it was an offering to Poseidon, god of the sea (whose symbol was a horse), the Trojans dragged the device into their own city.

Trojans watch as Greek fleet departs by night.

The Trojans celebrated what they thought was the end of the war. Later, as they slept, the Achaean heroes within the horse climbed down and opened the gates. The Greek army had silently returned, and waited in the darkness outside. The gates open, the Achaean army rushes in. The city falls, and is subject to vicious sack and slaughter. In the end, only women are spared; the men and children being put to the sword. In the Mycenaean world of Bronze Age Greece, women were useful as household slaves; being put to work doing the myriad of chores necessary to the maintenance of palace life. Noble women taken as concubines were valued trophies of war, a symbol both of a hero’s martial success and manly virility.

The Trojans celebrated what they thought was the end of the war. Later, as they slept, the Achaean heroes within the horse climbed down and opened the gates. The Greek army had silently returned, and waited in the darkness outside. The gates open, the Achaean army rushes in. The city falls, and is subject to vicious sack and slaughter. In the end, only women are spared; the men and children being put to the sword. In the Mycenaean world of Bronze Age Greece, women were useful as household slaves; being put to work doing the myriad of chores necessary to the maintenance of palace life. Noble women taken as concubines were valued trophies of war, a symbol both of a hero’s martial success and manly virility.

Sack of the city, from “Troy” (2004)

For a scholarly look at the subject matter, visit Minoan Linear A, Linear B, Knossos & Mycenae

Some of the artwork in this article has been reproduced with the permission of Osprey Publishing, and is © Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

www.ospreypublishing.com

____________________________________________

–Top Image Title and Credit:

Hi Kathleen, I love this post . Barry Jacobsen’s blog posts are always outstanding. Will Re-blog.!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Rita!

LikeLike

A fabulous post, thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] was like going back to the Mycenaean Period. They had placed them by hand in the walls of the tombs and we were taking them out by hand,” […]

LikeLike