One fine day in February 1902, while building a new farmhouse on his land near Monteleone di Spoleto, Italy, Isidoro Vannozzi happened upon a burial mound covering a subterranean tomb.

Venturing inside, Vannozzi and his son found a human male skeleton in the burial chamber, as well as a ramshackle mess of corroded bronze and iron objects, the largest of which turned out to be a dilapidated bronze parade chariot. Two additional skeletons, a man and a woman, were discovered in an adjoining tomb with additional bronze grave goods nearby.

Today, the spectacularly restored Etruscan bronze chariot from the 6th century BCE found on Vannozzi’s property ranks among the premier archaeological finds in the world. Depicting scenes from the life of Achilles, the chariot proudly displays Thetis’ presentation of the divine armor created by Hephaistos, with a stunning Shield of Achilles occupying the center stage.

In 1902, however, the hapless Vannozzi was less than impressed with the rusting pile of junk in the front yard of his new building. Calling for two men and a truck (more likely an oxcart?), he sold all of it for the price of scrap iron and used the sale price of 950 Lire (equivalent to about $6,000) to buy roofing tiles for the new family farmhouse.

From the hands of the junk dealer, the decayed and damaged parade chariot swiftly ascended the ranks of more knowledgeable Italian buyers and antique dealers. Emerging onto the Paris art market in 1903, the bronze chariot from pre-Roman times was purchased by General Luigi Palma di Cesnola, the founding director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Egyptian Chest from the tomb of the Valley of the Kings, ca. 1350 BCE depicting King Tutankhamen battling the Asians. Source: Wikimedia Commons

When Chariots Originally Emerged Onto the Weapons Market

Originating in the ancient Near East, chariots emerged onto the weapons market in the 2nd millennium BCE. Soon the adoption of chariots began spreading to the West by way of Egypt and Cyprus, fanning out into the Greek world, extending well into Italy, and on into Europe.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the majority of chariots found on the Italian peninsula were produced in Etruria between the 2nd half of the 8th and the 5th centuries BCE. Of the various types of chariots that have been found on the peninsula, however, none appear to have been used in warfare.

Belonging to a class of exclusive parade chariots, the Monteleone chariot, as it is now known, spaciously accommodates an aristocratic owner and his driver. Equally magnificent horses would certainly have been employed to draw the impressive chariot and its owner, with the horses standing about 49 inches (122 cm) apart from each other at the point where the yoke rested on their necks.

Detail View of The Monteleone Chariot depicting Thetis presenting the new armor to Achilles. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A Spectacular Showcase for the Shield of Achilles

Appearing in public only on special occasions, the Monteleone chariot must have been a beautiful sight worth waiting for. Every centimeter of bronze surface has elaborate repoussé embellishments, rendered from the famous ancient Greek legends and artistic representations of the Trojan War that were equally beloved throughout Tuscany

On the chariot’s taller front panel, standing in profile and facing each other, Thetis is presenting Achilles with his new divine shield and helmet to replace the set stripped from the slain Patroklos. Two birds of prey are attacking a wild boar which has attacked a deer. The boar is actually separate from the front panel, situated on the chassis at the point where the pole extends out from the car.

The two battling warriors on the right side panel are identified as Achilles and Memnon fighting over the slain body of Nestor’s son Antilochos, who had taken over as Achilles’ chariot driver after the death of Patroklos. According to Proclus’ Summary of the Aithiopis, Achilles avenges Antilochos by killing Memnon, but is soon afterwards killed by the Trojan prince Paris Alexandros.

Detail View of the right side panel of the Monteleone Chariot depicting Achilles defeating Memnon. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The left side panel depicts Achilles’ apotheosis. Also recounted in the Aithiopis, Achilles is snatched from his funeral pyre by Thetis and, as depicted on the bronze side panel, he is transported beyond mortality to the White Island (Leukē) in a chariot drawn by two winged horses.

Beneath the soaring chariot is a woman, perhaps depicting Polyxena, fallen onto the ground and raising her left hand. Noted in the Aithiopis but covered in more detail by Euripides in his Trojan Women, Achilles appears in a vision at the end of the war and demands the human sacrifice of the Trojan princess Polyxena to bring on the winds needed for the Achaeans to sail for home. Polyxena readily agrees, preferring to die as a holy sacrifice rather than live as a debased slave.

Left Side Panel of Monteleone Chariot, depicting Achilles’ apotheosis.

Source: Mary Harrsch, Flickr

Revisiting the Monteleone Chariot’s First Reconstruction

Reflecting an intimate familiarity with the epics recounting the Trojan War, the Met likewise notes the artisan was strongly influenced by Greek art styles, in particular from Ionia and perhaps the island of Rhodes. The chariot’s repoussé panels are believed to have been produced in one of the Etruscan metal-working centers popular in the sixth century BCE, such as at Vulci.

Although the dazzling bronze chariot was originally decorated with inlaid ivory, amber, and other glamorous materials, only a handful of ivory embellishments have survived. These ivories are from both elephant and hippopotamus but are so fragmented that only the tusks of the boar at the base of the pole and the finials on the back of the chariot are situated in their original positions.

Of the original chariot’s wooden substructure, nothing remains beyond a bit of oak in the core of one wheel. The wheels were constructed of wood and revetted with bronze, which was a practice reserved only for more elaborate chariots. The floor of the car was constructed of wooden slats and the rails supporting the three bronze ornamental panels were originally from a yew or wild fig tree.

Wooden Substructure of a very similar Etruscan Chariot, ca. 550 BCE.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Leather was typically applied to the wooden substructure and the connection of the pole to the car was reinforced with rawhide straps. The pole itself was mounted on straight tree branches and the yoke was lashed to the pole with rawhide straps, as well.

Traces of the leather straps can still be seen on the upper end of the pole. The horses’ harness was also entirely made of leather, and washers of pigskin with the fat still attached were used between the moving parts of the wheels to help reduce friction.

In 1989, revisiting the chariot’s original 1903 reconstruction, the Metropolitan Museum began a time-consuming reexamination and restoration under the direction of Italian archaeologist Adriana Emiliozzi.

Over the many years required for the subsequent reconstruction, the Monteleone chariot was entirely dismantled. Suspicions were confirmed that the chariot had been originally assembled incorrectly and the careful reexamination has allowed many pieces to be relocated to their correct positions.

Coinciding with the completion of other major renovations, the newly restored Monteleone chariot served as a dazzling highlight of the Met’s grand re-opening of its Greek and Roman galleries on April 20, 2007.

Curator Carlos Picón, of the Met’s Greek and Roman department, glowingly refers to the magnificent Monteleone parade chariot as “the grandest piece of sixth-century Etruscan bronze anywhere in the world.”

The Monteleone Chariot, depicting Thetis presenting the new armor to Achilles. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A Bronze Chariot to Die For

Such a spectacular chariot is truly an object to die for. Or at least to die with. Clearly, the original owner of the Monteleone chariot preferred to be buried with this prized possession rather than bequeath it to a family member. The tomb that Vannozzi discovered beneath an unwanted hillock in front of his new farmhouse was purposely designed to sufficiently house both the chariot and the owner’s remains.

The hill site where the chariot was discovered, referred to as the Colle del Capitano, sits roughly 3,000 feet above sea level, and about two miles from the village of Monteleone di Spoleto. Today, the region is part of Umbria, about 55 miles southeast of Perugia. Historically, though, this mountainous region is known as Inner, or Upper Sabina, the northern part of the ancient region inhabited by the Italic tribe of Sabines.

Lying northeast of Rome in the heart of the Apennines, the site of the pre-Roman Chariot Tomb on Vannozzi’s property is part of the necropolis of a settlement discovered higher up above the village, on Monte Pizzoro. Archaeologists date the burials here from the Bronze and Early Iron Ages, i.e., the end of the 12th – 10th century BCE, as well as from the 6th century BCE.

View of Monteleone di Spoleto, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Nearby tombs dating in the 6th century BCE were typically dug into the rock, which makes the similarly dated Chariot Tomb all the more significant for its well-designed architecture and bronze grave goods, especially the stunning bronze chariot.

The occupant of the Chariot Tomb, according to Emiliozzi, “seems to have wielded the military, economic, political, and religious power of a Princeps.” The wealth of the chariot owner was likely derived from the strategic control of trade routes and key hubs in the road system between the Apennine Mountains and the passages through the valleys and flatlands down to the Adriatic coast.

Significant iron deposits in the area were likely known in antiquity, further enriching the local rulers and supplementing small-scale economic activities such as agriculture and sheep farming. Emiliozzi believes the beautiful bronze chariot may have been “a gift to win favor with a powerful local authority or to reward his services.”

Endowed with the power, wealth, and status of royalty, the owner of the Monteleone chariot was clearly highly educated as well. Employing a burial custom no longer practiced in Etruscan and Latin urban areas of the 6th century BCE, all of the traditional cultural features of a chariot burial were present in the Monteleone Chariot Tomb.

In addition to weapons, Emiliozzi reports, there were grave goods associated with banquet and symposium rituals, and, above all, the actual burial rite of interring the owner’s chariot in the tomb with the remains of the deceased.

1902 B&W Image of Monteleone Chariot Tomb Grave Goods Before Leaving Italy. Source: Martin Conde, Flickr

The Metropolitan Museum Acquires the Monteleone Chariot

Adriana Emiliozzi relates the unfortunate case of Isidoro Vannozzi after the Italian farmer stumbled upon the Chariot Tomb with its skeletons and bronze burial goods. “In late March,” says Emiliozzi, “he took samples to Norcia to show a junk dealer, Benedetto Petrangeli, who in next to no time tricked Vannozzi into selling him everything for the price of scrap iron, that is, six soldi a kilo, for a total of 950 lire (approximately $6,000).”

Two months after the discovery of the Chariot Tomb, the Italian authorities launched an investigation that was, unfortunately, fraught with delays, miscommunication, and blatant errors. It wasn’t until June that archaeologist Giulio Emanuele Rizzo drafted his report after collecting information intended to help the authorities recover the items and prevent them from leaving Italy.

During this time, Emiliozzi continues, “Petrangeli contacted the Roman antiques dealers and, after much hesitation because he was not sure he was getting the best price, sold the pieces to Ortensio Vitalini for the sum of 150,000 lire (about $1.7 million today).”

In spite of the Italian authorities’ investigation, Vitalini stealthily sent the disassembled chariot and other grave goods to Paris in February 1903, where he deposited the best pieces in the vaults of Crédit Lyonnais. In April 1903, everything was surreptitiously shipped to the US after an undisclosed purchase price was agreed upon between Vitalini and Luigi Palma di Cesnola of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Attic Black-Figure Amphora ca. 530 BCE, depicting the suicide of Telamonian Aias (Ajax) after Odysseus wins Achilles’ armor. Source: Wikimedia Commons

(note the similar Gorgon head on this shield and the Monteleone Chariot)

Monteleone vs The Met: Revisiting Ajax vs Odysseus?

An ironic comparison between Isidoro Vannozzi and Sophocles’ Telamonian Ajax comes to mind here. Vannozzi surely must have experienced something of Ajax’s overwhelming grief over the loss of Achilles’ armor when he learned the incredible value of his rusting pile of “scrap metal.”

Perhaps the communal sense of injustice that has arisen in Italy over the loss of Monteleone’s fabulous chariot to the Metropolitan Museum of Art has its roots in Vannozzi’s anguish.

Demands for repatriation of the chariot practically since its clandestine transfer to the US have met with little success. In February 1904, citing a heated debate in the Italian Parliament over the sale of the chariot, the New York Times raised questions about the chariot’s “surreptitious exportation to the United States” and concluded that the “loss to Italian archeology was incalculable.”

A life-size replica of the chariot was presented by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to the city of Monteleone in the mid-20th century but the repatriation movement continued growing. In 2006, the Met repatriated 21 Italian objects after they were cited as evidence in a lawsuit involving stolen antiquities. After this, the repatriation movement for the Monteleone chariot, or Biga, gathered steam and came to a head in 2007.

“Over My Dead Body!”

Attic Black-Figure Oinochoe ca. 520 BCE, depicting Odysseus and Aias (Ajax) quarreling over Achilles’ armor.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Pressing a lawsuit against the Met, Monteleone Mayor Nando Durastanti retained the services of Tito Mazzetta. Mazzetta, a lawyer from Atlanta, Georgia, whose family emigrated from Monteleone, agreed to take the case pro bono.

According to a press release dated April 20, 2007 by the Comune di Monteleone di Spoleto, the lawsuit was boldly challenged by the Met’s director:

Alla prima lettera di Mazzetta, il direttore del Met ha risposto: “Se volete la biga, dovete passare sul mio cadavere!”.

[poorly translated from Italian to English by Google: At the first letter from Mazzetta, the Met manager replied, “If you want the big lady, you have to pass on my corpse!” (probably more like: “Over my dead body!”)]

Expressing the sentiment more diplomatically, Met Spokesman Harold Holzer states that the chariot was “purchased in good faith.” Holzer adds that, under the Met’s care, the chariot has been “lovingly preserved, widely published and seen by millions of visitors from around the world.”

Mayor Durastanti responds, “I’m very sorry for the Met because they’ve done a great job in making the most of the chariot. It’s clear they care a lot about it, but it’s ours. It’s part of our identity.”

Echoes of an ancient argument rise on the pine-scented breeze wafting through Monteleone di Spoleto. The angry voice of Telamonian Ajax, offended by the political machinations of Athena and the Achaean Generals, can be heard once again, lashing out impotently over his loss of Achilles’ divine armor to the wily Odysseus.

The case didn’t work out well for Ajax. And it appears that the Shield of Achilles is defiantly proving once again its extraordinary value—truly a shield worth dying for, even embellished on an Etruscan bronze parade chariot, as in this underdog case of Monteleone vs the Met.

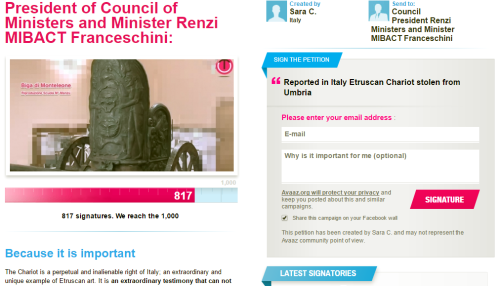

Sign the Petition to Return the Monteleone Chariot to Italy

Please consider signing the online petition to return the Monteleone chariot, or Biga, to Italy. (Use google.translate.com to translate the page from Italian to English).

Published on Avaaz.org on October 5, 2014, this petition is addressed to Italian President of Council of Ministers and Minister Renzi MIBACT Franceschini. Learn more about the grassroots Italian effort to return the chariot (in Italian) by clicking here.

At the time I signed the online petition, 818 signatures had been received, with a total of 1,000 desired. Please click the image if you are interested in signing.

Screenshot of avaaz.org petition to repatriate the Monteleone Chariot.

Please click to sign!

(Uploaded to YouTube on Dec 4, 2007 by jsneeky43}

You are doing and incredible job. I am amazed by your posts; there are a lot of them – all of them so well documented!

I love your matter; maybe because I have always felt a little like Patroclus -and thus a virtual lover of Aquilles 🙂 -not Brat Pitt! … Aquilles-. I like a lot all these stories, Kathleen. Honest! (and I’m somewhat knowledgeable in Art, History and Classical Philology, in spite of my juvenile looks 🙂 Best regards 💜

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Li, It’s my favorite subject and I’m delighted to know you share this love, too! Best wishes, to you, too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re dearly welcome! About your subject… who couldn’t love it ! It’s in the very root of our art and culture . Warm hugs from here (Catalunya) – a nation grown from Greek culture, among several others…, but anyway very Greek :))

LikeLiked by 1 person

We have so much to thank the Greeks for, don’t we?! btw I really enjoyed Barcelona when I visited (quite some time ago, tho) – I have many wonderful memories of Spain!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with the first commenys (and I thank you for your response again and you fondness of Barcelona)… But, please, understand that we are not Spaniards, and our homeland is NOT at all the ****** Spain :)) Sorry for my roughtness about this, but we are sick and tired of everything about Is-pain after five centuries of enduring its ways 😦

LikeLike

I regret my many faults and typos in the comment above 😦 I’m sorry ! Nite nite !

LikeLiked by 1 person

No worries, I enjoy your visits!

LikeLike

Hi Kathleen, I thoroughly enjoyed this post because the last term of my study was all about the Military sector in the Greek Mycenaean period and of course involved chariots. However most were made of wicker wood and covered with hide,there were also bronze chariots My study is the Linear B script writings. Thank you for visiting my blog btw.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Rita. I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog, your fascinating life interests, and the way you are sharing your knowledge and progress with us!

My next post, working on pushing it out tonight, is a guest post from Richard Vallance on the Linear B records of chariots in the Knossos armory. I’m working towards a finer understanding of Mycenaean warfare and weapons, so your work in this area is very exciting to me, too.

I’d be honored to feature a guest post from you, too – please feel free to suggest your favorite choice if you have something I can repost or feel free to write something new. I’d love to share your excellent work here!

LikeLike

Hi Kathleen, I have just read your guest post for Richard Vallance and thanks for the mention. Also thank you for your invite as a guest. If you can give me a little time I will try to think of something which maybe of interest to you. One thing is, I have just completed an essay about Linear B which will be going onto Academia shortly but its quite lengthy so maybe a little too long because it involves some illustrations. Let me know what you think. Best wishes Rita. P.S. I am also enjoying your extremely interesting posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Rita, it’s my pleasure to give you a shout out, too! I’d love to read your article on Academia, lengthy is never a problem, especially if it includes illustrations since they add so much value to an article.

Take your time, no hurries no worries, you’re always welcome here anytime for any reason! Happy Weekend!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] a wine cellar when he accidentally came across the item in 1902. Vannozzi only earned about $6,000 in today’s money for selling the chariot he found, even though it was ultimately sold for $1.7 million in […]

LikeLiked by 1 person